Quality improvement measures for increasing the colorectal

cancer screening rates at a community health center

As a part of A.T. Still University, students become members of a community with a rich history of whole-person healthcare, focusing on the influence of body structure on function, on the body’s innate ability to heal itself, and on the connection between the body, mind, and spirit.

In whole-person health care, the focus is on the person, not the disease. There is a recognition that the complex factors that cause disease, illness or physical imbalance may stem from a variety of issues related to the body, mind or spirit,.

By helping the person attain better health on a more holistic level, the specific illness can be addressed, while the overall benefits of whole-person healthcare will last a lifetime. This focus on healthcare over “sick care” is fundamental to the SOMA curriculum.

Purpose

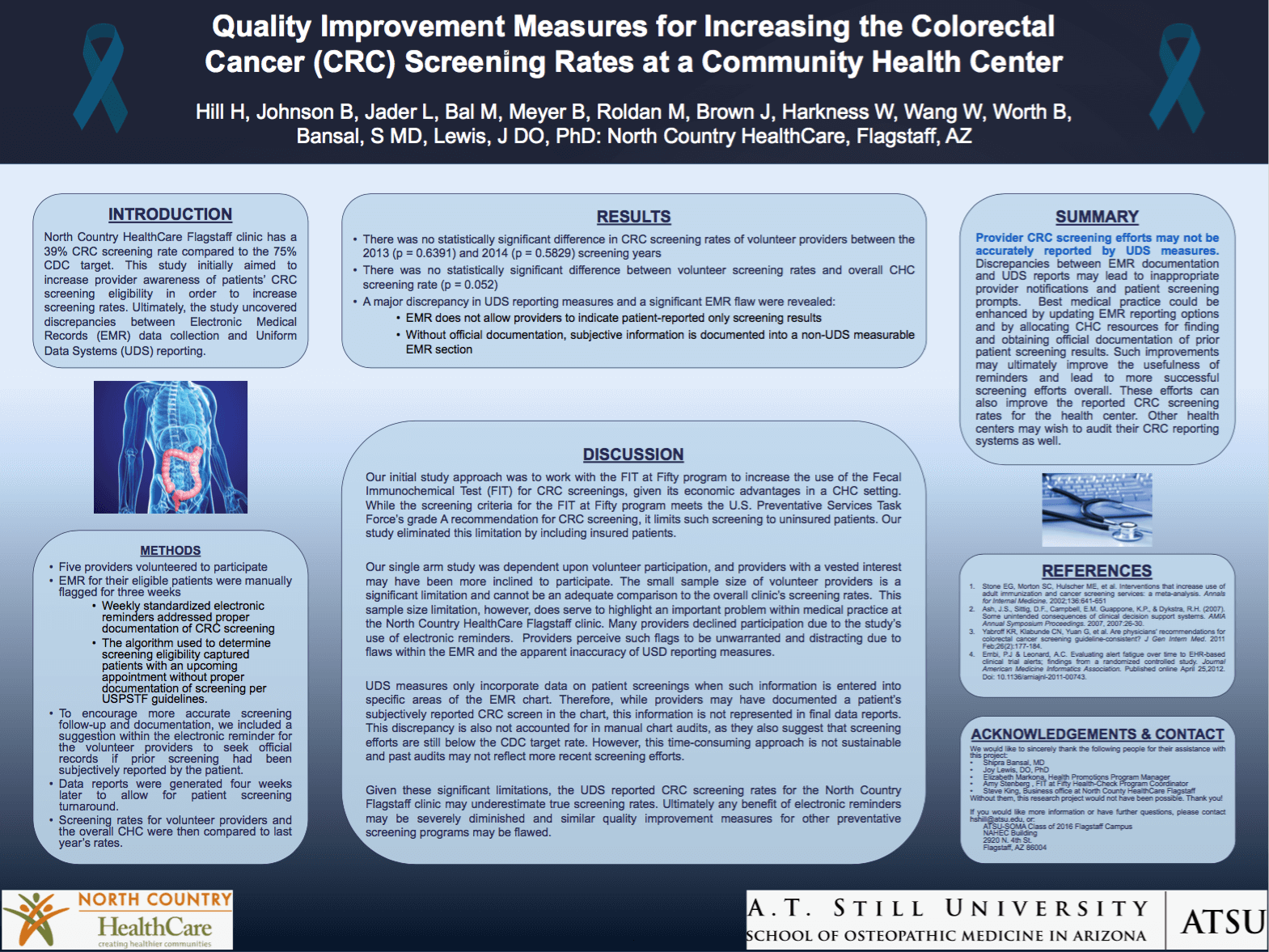

North Country HealthCare Flagstaff clinic has a 39% CRC screening rate compared to the 75% CDC target. This study initially aimed to increase CHC provider awareness of patients’ CRC screening eligibility in order to increase screening rates. Ultimately, the study evaluated the accuracy of Uniform Data Systems (UDS), reporting measures.

Steps for Implementation

Study proposal was presented to North Country Flagstaff clinic providers. Five providers volunteered and the EMR for their eligible patients were manually flagged by researches for three weeks. Standardized electronic reminders addressed proper documentation of CRC screening and were applied to appointments in that upcoming week. The algorithm used to determine screening eligibility included EMR records with patient-reported prior screenings but no official documentation. Data reports were generated four weeks later to allow for patient screening turnaround. Providers were not identified on the reports. Screening rates for volunteer providers and the overall CHC were then compared to last year’s rates.

Benchmarks for Monitoring Results

There was no statistically significant difference in CRC screening rates of volunteer providers between the 2013 (p = 0.6391) and 2014 (p = 0.5829) time frames. There was also no statistically significant difference in overall CHC screening rates (p = 0.052). Discussion with providers and Community Health Programs at the health center staff revealed a major discrepancy in UDS reporting measures and a significant EMR flaw. The EMR does not allow providers to indicate when a screening result is patient- reported only. Without official documentation, providers incorporate this subjective information into an EMR section that is not UDS measurable.

Conclusions on Replicating this in Other Health Centers

Provider CRC screening efforts may not be accurately reported by UDS measures. Discrepancies between EMR documentation and UDS reports may lead to inappropriate provider notifications and patient screening prompts. Best medical practice could be enhanced by updating EMR reporting options and by allocating CHC resources for finding and obtaining official documentation of prior patient screening results. Such improvements may ultimately improve the usefulness of reminders and lead to more successful screening efforts overall. These efforts can also improve the reported CRC screening rates for the health center. Other health centers may wish to audit their CRC reporting systems as well.

Limitations

Our initial study approach was to work with the FIT at Fifty program to increase the use of the Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) for CRC screenings given the economic advantages of this test in a CHC setting. While the screening criteria for the FIT at Fifty program meets the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force’s grade A recommendation for colorectal cancer screening, it limits such screening to uninsured patients. Our study eliminated this limitation by including insured patients. Furthermore our electronic reminders ultimately did not focus on screening patients with the FIT alone.

Our single arm study was dependent upon volunteer participation. Providers with an invested interest in our study may have been more inclined to participate. The small sample size of volunteer providers is a significant limitation and cannot be an adequate comparison to the overall clinic’s screening rates.

This sample size limitation, however, does serve to highlight an important problem within medical practice at the North Country HealthCare Flagstaff clinic. Many providers declined participation due to the study’s use of electronic reminders. Providers perceive such flags to be unwarranted and distracting due to flaws within the EMR and the apparent inaccuracy of USD reporting measures.

Indeed, UDS measures only incorporate data on patient screenings when such information is entered into specific areas of the EMR chart. Therefore, while providers may have documented a patient’s subjectively reported CRC screen in the chart, this information is not represented in final data reports. The FIT at Fifty program has performed chart audits in the past in order to account for this discrepancy. These audits seemed to suggest that screening efforts were still below the CDC target rate. This time-consuming approach is not sustainable, however, and past audits may not reflect more recent screening efforts.

To encourage more accurate screening follow-up and documentation, we included a suggestion within the electronic reminder for the volunteer providers to seek official records if prior screening had been subjectively reported by the patient.

Given these significant limitations, the UDS reported CRC screening rates for the North Country Flagstaff clinic may underestimate true screening rates. Ultimately any benefit of electronic reminders may be severely diminished and similar quality improvement measures for other preventative screening programs may be flawed.