Increasing rural high school students’ knowledge in an effort to

improve motivation to pursue healthcare careers

The debates about solving the healthcare challenge in America are nearly as extensive as the problem itself. But sometimes action speaks louder than words. Many patients in underserved communities cannot afford quality healthcare. In partnership with the National Association of Community Health Centers, SOMA’s use innovative models to prepare students to meet the health care needs of society by placing them in medically underserved areas for their training.

After the first year of didactic classroom learning, students will experience hands-on training at one of several community clinics across the country. In this way, SOMA is able to deliver quality, affordable care to patients in need, while developing remarkable doctors with a mission to serve. It’s a practical solution that helps make a difference right now.

Purpose

To address the significant shortage of primary care physicians, we sought to:

- Gauge student interest in health care careers in a Health Professional Shortage Area

- Educate students regarding health care careers and health topics.

- Determine if this education affected students’ desire to pursue a health care Steps for Implementation, Champions and Resources

Steps for Implementation, Champions and Resources

- Organized high school visits with Western Brown biology teacher, Mrs. Amie Gardner.

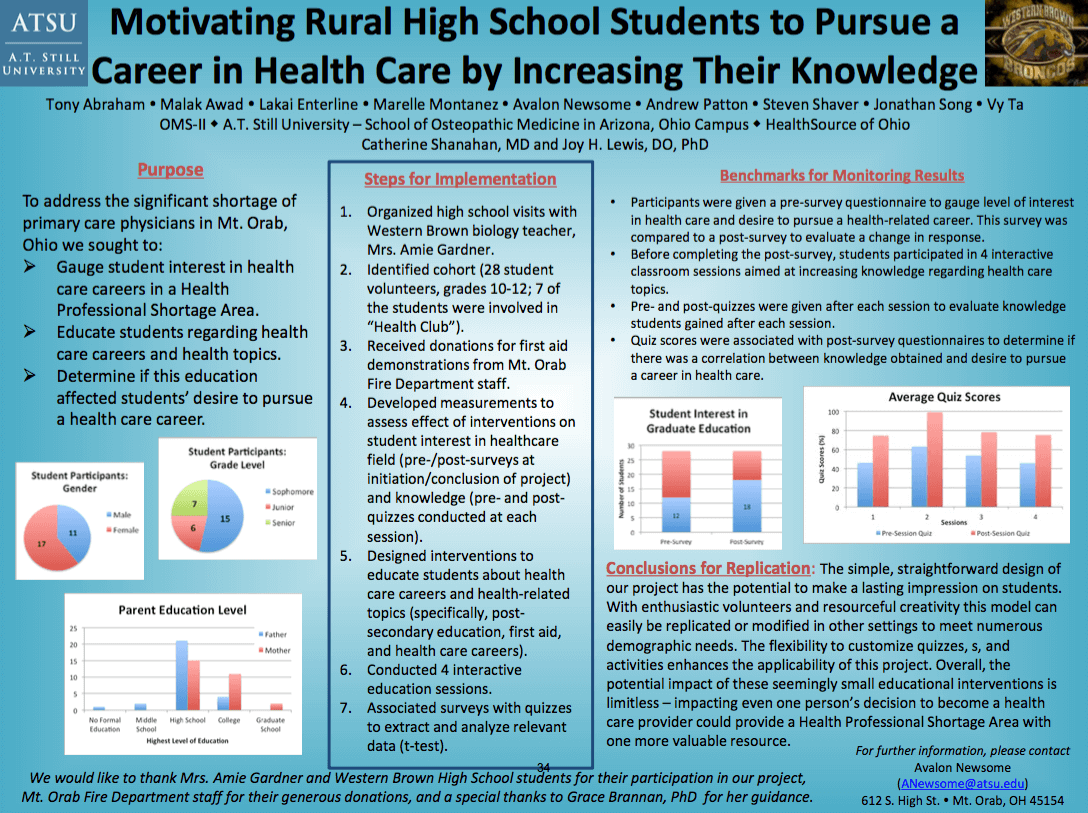

- Identified cohort (28 student volunteers, grades 10-12; seven involved in “Health Club”).

- Received donations for first aid demonstrations from Mt. Orab Fire Department staff.

- Developed measurements to assess effect of interventions on student interest in health care field (pre-/post-surveys at initiation/conclusion of project) and knowledge (pre-/post-quizzes each session).

- Designed interventions to educate students about health care careers and health- related topics (post-secondary education, first-aid, and careers).

- Conducted four interactive education sessions.

- Associated surveys with quizzes to extract and analyze relevant data (t-test).

Benchmarks for Monitoring Results

Participants were given a pre-survey questionnaire to gauge their level of interest in health care and desire to pursue a health-related career. This survey was compared to a post-survey to evaluate variations in response. Before completing the post-survey, students participated in four interactive classroom sessions aimed at increasing knowledge regarding health-related topics. Pre- and post-quizzes were given after each session to evaluate knowledge students gained before and after each session.

Finally, quiz scores were associated with post-survey questionnaires to determine if there was a correlation between knowledge obtained and desire to pursue a career in health care.

Conclusions for Replication

The straightforward, simple design of our project has the potential to make a lasting impression on students. With enthusiastic volunteers and resourceful creativity this model can easily be replicated or modified in other settings to meet numerous demographic needs, such as age, education level, and number of participants. The flexibility to customize quizzes, questionnaires, and activities enhances the applicability of this project. Overall, the potential impact of these seemingly small educational interventions is limitless – impacting even one person’s decision to become a health care provider could provide a Health Professional Shortage Area with one more valuable resource.

Limitations

One limitation of our study involves the population. Seven of the 28 or 25% of the participants were part of a Health Club; thus, the effectiveness of our intervention is skewed since these students presumably held pre-existing knowledge or interest in health care. The limited sample size, 28 students, also reduces the strength of our data. If more subjects were involved, the likelihood of attributing our results to chance would decrease. Our interventions occurred over a short time span; therefore, our surveys only reflect students’ interests within that brief time period. In addition, other possible influences, such as experiences outside of our sessions, could alter interest in the health care field, and these were not factored into our analysis.