Mara Havard, OMS-III, Ibraheim Ayub, OMS-III, Christina Cubillo, OMS-III, Grant Hughes, OMS-III, Cody Jackson, OMS-III, Travis Lundeen, OMS-III, Daimarys Perez, OMS-III, Shreyesi Srivastava, OMS-III, Racquel Valadez, OMS-III, Kendra Wang, OMS-III, Bradley Meek, DO, Mark Sivakoff, MD, Kate Whelihan, MPH, CPH, Joy H. Lewis, DO, PhD

Background

- The United States is currently experiencing significant COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy despite wide availability and accessibility to the vaccine.

- Many studies suggest that Hispanic/Latino individuals are less willing than Whites/Caucasians to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.1,2

- Studies have also shown that women are more hesitant than men to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.3

Objectives

This study explores vaccine hesitancy and barriers to immunization among minority groups at Adelante Healthcare, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), in Maricopa County, Arizona.

Methods

- A voluntary multiple-choice survey was developed to 1) determine vaccination status and 2) explore reasons why patients have or have not received the vaccine. Surveys (n=3,150) were distributed to patients at seven Adelante Healthcare clinics within Maricopa County, AZ.

- Respondents were limited to patients who were 18 years or older.

- Data was analyzed by breaking participants down into subgroups such as ethnicity, age, and gender.

Results

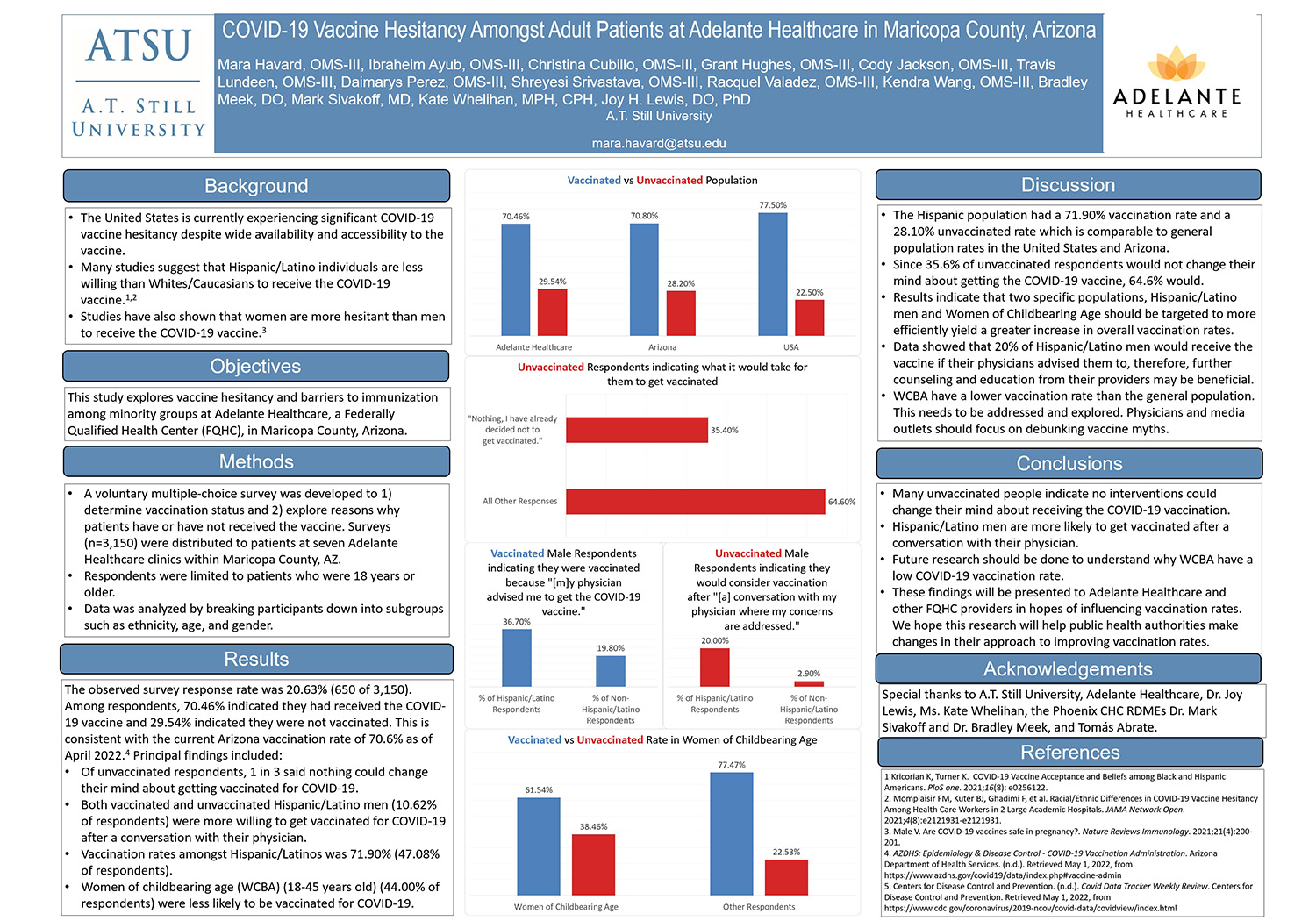

The observed survey response rate was 20.63% (650 of 3,150). Among respondents, 70.46% indicated they had received the COVID-19 vaccine and 29.54% indicated they were not vaccinated. This is consistent with the current Arizona vaccination rate of 70.6% as of April 2022.4 Principal findings included:

- Of unvaccinated respondents, 1 in 3 said nothing could change their mind about getting vaccinated for COVID-19.

- Both vaccinated and unvaccinated Hispanic/Latino men (10.62% of respondents) were more willing to get vaccinated for COVID-19 after a conversation with their physician.

- Vaccination rates amongst Hispanic/Latinos was 71.90% (47.08% of respondents).

- Women of childbearing age (WCBA) (18-45 years old) (44.00% of respondents) were less likely to be vaccinated for COVID-19.

Discussion

- The Hispanic population had a 71.90% vaccination rate and a 28.10% unvaccinated rate which is comparable to general population rates in the United States and Arizona.

- Since 35.6% of unvaccinated respondents would not change their mind about getting the COVID-19 vaccine, 64.6% would.

- Results indicate that two specific populations, Hispanic/Latino men and Women of Childbearing Age should be targeted to more efficiently yield a greater increase in overall vaccination rates.

- Data showed that 20% of Hispanic/Latino men would receive the vaccine if their physicians advised them to, therefore, further counseling and education from their providers may be beneficial.

- WCBA have a lower vaccination rate than the general population. This needs to be addressed and explored. Physicians and media outlets should focus on debunking vaccine myths.

Conclusions

- Many unvaccinated people indicate no interventions could change their mind about receiving the COVID-19 vaccination.

- Hispanic/Latino men are more likely to get vaccinated after a conversation with their physician.

- Future research should be done to understand why WCBA have a low COVID-19 vaccination rate.

- These findings will be presented to Adelante Healthcare and other FQHC providers in hopes of influencing vaccination rates. We hope this research will help public health authorities make changes in their approach to improving vaccination rates.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to A.T. Still University, Adelante Healthcare, Dr. Joy Lewis, Ms. Kate Whelihan, the Phoenix CHC RDMEs Dr. Mark Sivakoff and Dr. Bradley Meek, and Tomás Abrate.

References

1.Kricorian K, Turner K. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Beliefs among Black and Hispanic Americans. PloS one. 2021;16(8): e0256122.

2. Momplaisir FM, Kuter BJ, Ghadimi F, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Health Care Workers in 2 Large Academic Hospitals. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(8):e2121931-e2121931.

3. Male V. Are COVID-19 vaccines safe in pregnancy?. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2021;21(4):200-201.

4. AZDHS: Epidemiology & Disease Control - COVID-19 Vaccination Administration. Arizona Department of Health Services. (n.d.). Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.azdhs.gov/covid19/...;

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Covid Data Tracker Weekly Review. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronaviru...;